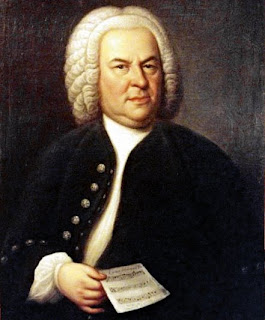

Only once in his lifetime did Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) pose for a painter but it is known that, being a busy man, he actually left the workshop before the end of the session! So even though Haussmann's painting (1748, right) is the best we have, it remains very unreliable. This could have been the end of Bach's iconography, but it is not. In 1895 Bach's body was exhumed, and a sculpture made from his skull (below; recently, a Scottish anthropologist made a computer-modeled reproduction of Bach's bust, shown on the right below).

Only once in his lifetime did Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) pose for a painter but it is known that, being a busy man, he actually left the workshop before the end of the session! So even though Haussmann's painting (1748, right) is the best we have, it remains very unreliable. This could have been the end of Bach's iconography, but it is not. In 1895 Bach's body was exhumed, and a sculpture made from his skull (below; recently, a Scottish anthropologist made a computer-modeled reproduction of Bach's bust, shown on the right below).Imagine that: you come out of your mother's womb, you do your thing, you die. So far so good. But 145 years after your burial, someone removes your body from your grave in Leipzig to look at the shape of your skull and try to figure out what you might have looked like during your time! You'd agree that would be surprising.

But in fact, in the case of Bach, there was a catch: when I said he did his thing, that would be an euphemism to say that was an euphemism. After his death, even though he never thought his music would survive him, but rather that other composers will simply replace it by their own compositions, he came to be considered as the greatest composer that ever lived by such people as Mozart, Chopin, Liszt, Wagner, Debussy, etc.

Bach's musical involvement was absolutely permanent. Jack Gibbons (the pianist-lecturer of that evening) used the -- somewhat dubious -- image that if you were to copy every note he's ever written, you wouldn't achieve it in your lifetime ("Think about it for a minute," he added with humour). Bach must have been mostly writing in one throw, without any correction. Add to this his numerous administrative duties (he even had to teach Latin during his last position in Leipzig, where he was taken only as a third choice!), his immense family of twenty or so children, and you have the picture of an extremely productive composer sleeping barely a couple of hours every night.

Bach's family was so musical that they had it in their blood: a usual Sunday afternoon leisure was to improvise fugues on popular themes, an very technical exercise! (The last of the Goldberg Variations is an illustration of these "games.") The word "Bach" was practically a synonym for "Musiker" (By the way, the equivalence in England was the Gibbons family -- and Jack Gibbons to add that it is not known if there are any living descendants nowadays... (I can think of Beth Gibbons at least.))

I've admired the effects of such a pure dedication to music in a documentary about Ravi Shankar. I had been struck by the fact that most (if not all?) of his children decided to become musicians (his daughter Anoushka Shankar who plays the sitar too, and also of course Norah Jones). The intensity of his passion was powerful enough to diffuse to his children. The documentary had a magical scene where he gives a concert with Anoushka and during his solo you can see her face illuminating by delight and surprise.

[There I saw the beauty of the (rather old-fashioned) tradition of a family business: the son of the baker become a baker and so on. It is sad if this continuation is due to some kind of inertia, but it can also be due to a sincere love of work, a proudness and joy of creation, which acts as a positive force (rather than a negative constraint) on successive generations... The example of Ravi Shankar is less ambiguous here, as his own parents were not musicians, so that the choice of becoming musician was less automatic than in Bach's family.]

Bach's first wife died as he was on a trip, and he found her buried when he came back. He was however to find love again in Anna Magdalena, which was 17 years younger than him. They had a very joyful marriage, as JG illustrated by playing one of the French Suites, if I remember correctly. He said Anna was also an accomplished musician (which is a bit in contradiction with the technical ease of the Notebüchlein für Anna Magdalena Bach...). Their passion for music was so fusional that Anna ended up having the same handwriting than her husband, for the greatest confusion of modern musicologists.

The second part of the lecture-concert was devoted to the famous Goldberg Variations (1741). Bach composed them by the request of a Russian Ambassador, Count Kaiserling, who wanted to be distracted during his long nights of insomnia. Goldberg was the name of the Count's personal musician (his Hi-Fi set in some sense), who must have damned Bach every time he had to get up in the middle of the night to play those amazingly hard variations. It is fascinating to imagine the sleepless Count meditating on the infinite depths of the Variations in the darkness of his luxurious room...

Bach died of the sequels of disastrous eye surgery operations. As his blindness was keeping him away from his work, he decided to precipitate a second operation very shortly after the failure of the first. Several months later, he suddenly recovered his full vision for a few hours and then died.

No comments:

Post a Comment